Din the Norwegian mountains, amid a vast expanse of shining snow and howling winds, Toralf Mjøen throws a piece of meat into a fenced enclosure and waits for a pair of dark eyes to emerge from the snowy lair.

These curious and playful arctic foxes know Mjøen well. He has been a caretaker at this breeding facility for 17 years, climbing the mountain every day to feed them in their enclosures near the small village of Oppdal, about 250 miles north of Oslo.

But Mjøen’s familiarity with the species stretches back much further, from his years working on his father’s fox farm, where they bred the animals for their fur.

Now, years after the fur farms have closed, the arctic fox has become a symbol of conservation in Norway. Its long-term fate here, however, is still in doubt.

“Sometimes,” Mjøen says, “there’s nothing we can do but try.”

Saving an animal from extinction is often seen as a series of dramatic steps, such as a ban on hunting, to bring a species back from the brink of oblivion. But for Arctic foxes and many other recovering but still fragile animal populations around the world, Mjøen says, “It’s about baby steps.”

Every year since 2005, the Norwegian breeding program has released foxes born in captivity into the wild. Measured strictly by numbers, it works: the population of arctic foxes has increased more than tenfold and they have spread to Finland and Sweden.

But the research team leading the recovery project still feel they are far from the finish line. Especially during the last five years, killings of golden eagles at the breeding station and increased inbreeding in the wild have complicated the rescue operation.

“The problems we are facing today are actually because of the success of the program,” says project leader Craig Jackson of the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA).

In the first decade, scientists were so focused on raising the numbers that they started with a population of about 50 foxes and bred them to more than 550 spread across Scandinavia, with about 300 in Norway.

But now, he says, “It’s not just about producing foxes.” Instead, the goal is to increase genetic diversity in the population to make animals more resilient to food shortages and climate change.

The project now meets all but one of the most important criteria for success in a reintroduction program, according to a study by Jackson’s team published in 2022. The reintroduced foxes are reproducing faster than they are dying, a sign of good.

But there is still one big problem: they are still unable to sustain themselves without human intervention, depending on supplemental nutrition and lack of genetic resilience.

The only way to create more resilience is to rebuild the genetic diversity that was lost when the Norwegian population crashed decades ago, Jackson says.

He explains that arctic foxes prey on lemmings, a small rodent with a fluctuating population. Foxes have been particularly hard to find in recent years because the warming climate has created more opportunities for an invasive competitor: red foxes.

Although red foxes were killed in Norway as an early measure to help Arctic foxes recover, they still compete. The lack of rodents has made it more difficult for arctic foxes to become a self-sustaining population.

If there are years with low lemming numbers, Jackson says, a genetically diverse group of foxes is more likely to survive because they are healthier and can compete for resources.

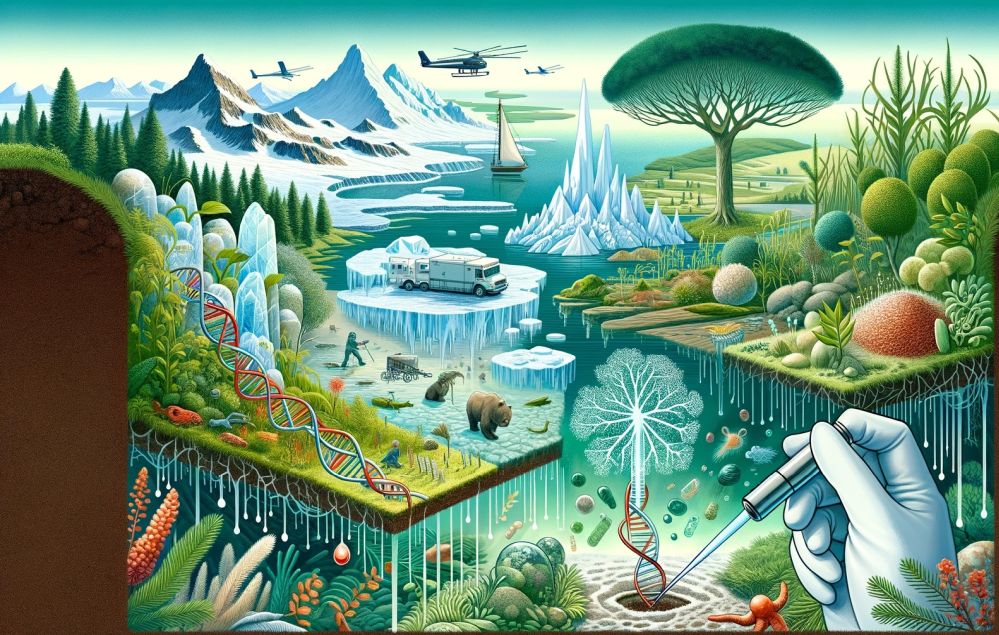

Jackson’s team is trying to build diversity by introducing genetically distinct foxes into specific areas. But the fox’s deeply fragmented habitat makes this more challenging: they need to know exactly which wild fox groups lack diversity in order to know where to release the captive-bred foxes.

Øystein Flagstad, geneticist for the captive breeding project, says it requires monitoring of all wild and released foxes to assess not only their numbers, but also their genomes.

Predation by golden eagles highlights another complication in captive breeding programs: as the animals must be concentrated in enclosures, they become more vulnerable to predators and disease.

According to a study published last year, Jackson’s team has been forced to get creative in trying to thwart the Golden Eagles. Now, the fences are filled with bamboo sticks and ropes, but this has not been enough.

Since 2019, the captive breeding facility, which usually has about 16 foxes, has had 11 deaths, nine of which have been confirmed to be caused by golden eagles. Jackson, relying on dozens of live camera feeds, tries to monitor the foxes from his office in Trøndheim, north of the breeding station.

In January, Jackson logged on to check the live cameras when he saw an eagle waiting for a male fox. He hurriedly called Mjøen, the caretaker, but it was too late. In the video clip, an arctic fox looks small and vulnerable to the powerful talons of a golden eagle.

Losing just one fox to an eagle means losing an investment of hundreds of thousands of Norwegian kroner, says Tomas Holmern of the Norwegian Environment Agency, which has funded the station since 2006 at an annual cost of about 3.1 million kroner ( £230,000). The program aims to improve the status of Norway’s fox population from endangered to merely vulnerable by 2034, and its funding is guaranteed until 2026.

A conservation biologist, Holmern cited other captive breeding programs, such as black-footed ferrets in the American West and the California condor, as examples of successful conservation efforts at improving a species’ genetic diversity.

In these cases and many others, the main obstacle is what conservation biologists call “genetic bottlenecks,” which occurs when a population is reduced to a few individuals and loses its genetic diversity.

Building genetic variation to a healthy level in a species can take thousands of years, says Klaus Koepfli, a geneticist at George Mason University’s Smithsonian School of Conservation in Virginia, who has worked with black-footed ferrets. “That doesn’t stop us from trying,” he adds.

Black-footed reindeer, he says, are still considered a conservation-dependent species because – like arctic foxes in Norway – they need people to keep their numbers up. If scientists stood back and let nature take its course, ferrets probably wouldn’t survive.

A relatively new tool that can speed up the recovery process is gene editing, which allows scientists to make changes to DNA that would otherwise take hundreds of generations, and is now thought to restore genetic diversity and repair mutations in some species. harmful.

“Whether you’re talking about fish, birds, mammals or lizards, we can use the same tools for all those species,” says Koepfli.

Even amid all the concern about the threats facing Arctic foxes, there are signs of hope. And some of those marks are imprinted in the snow: fresh tracks from a wild fox, discovered in April. It’s a male and he’s been roaming the breeding station. Inside the enclosure is a female who lost her mate to an eagle in January.

Find more Age of Extinction coverage here and follow Biodiversity Reporters Phoebe Weston AND Patrick Greenfield on X for all the latest news and features

#Eagle #attacks #red #invaders #genetic #barrier #fight #save #arctic #foxes

Image Source : www.theguardian.com